Continued from part one…

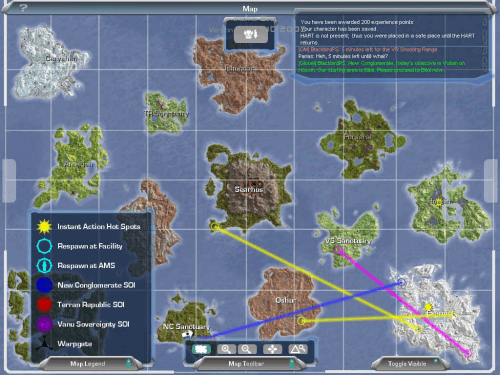

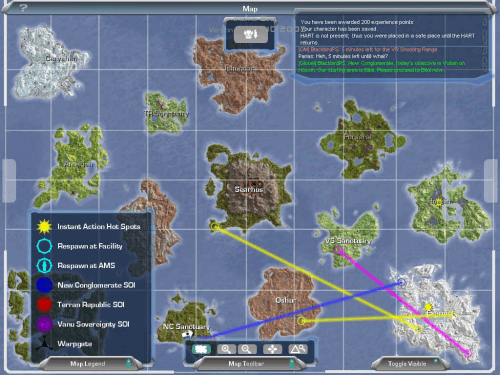

“Auraxis, as it looked before The Bending.”

When talking about how to get to the action in the last article I made passing mention of connections between warp gates and “spheres of influence” so let’s expand on that and go over the all-important map. In addition to those empire sanctuary islands, Auraxis was made up of ten continents of similar size and various biomes. Those continents were connected to each other via the same type of warp gates that connected some of them to sanctuary islands. Each continent was a massive, expansive land of a size and scale that is pretty much unheard of for an FPS game. While it might blow other sandbox FPS games out of the water in size, the world is pretty empty, with the only real points of interest outside of the occasional bridge or bunker being the facilities and the small guard towers near them, which are ultimately what we’re fighting over.

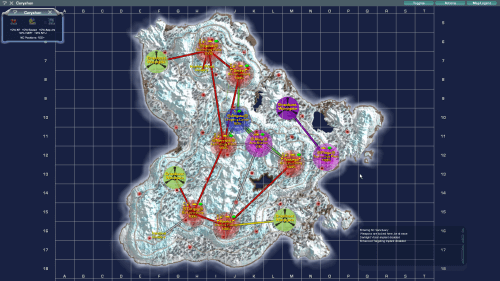

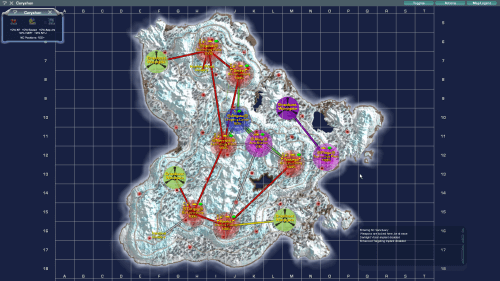

“Ceryshen’s continental map. Mostly controlled by the TR at the moment.”

Like the connections between continents, each facility was connected to at least one other facility on the continent, forming a “lattice” structure. The “lattice links” between these facilities were important in defining the battlefronts – your empire could only attack an enemy owned facility it had a link to, either by facilities you’ve captured, or by a warpgate connected back to your empire’s sanctuary or another continent you control. Thanks to these defined battlefronts, battles were mostly concentrated around these areas, helping keep the player population from being spread too thin. The continental lattice also provided benefits from facilities of certain types under your control. For example, if you were at a friendly facility that was connected to a tech plant your empire owned, you could spawn more advanced vehicle types from its vehicle terminals. This added a little bit more strategic consequence into decisions about which facility your empire should attack, and in what order, whether it be to gain those benefits or simply take them away from your enemies.

As for the sphere of influence, this was simply an area around a facility or a tower that was “controlled” by the empire that owned that facility or tower. This area could not be directly dropped on (as mentioned) and enemy Combat Engineers couldn’t fill them with their own deployable equipment. The area also more generally functioned roughly as a mini “zone” in the traditional MMORPG sense, so things like how experience points for battles over the control of these facilities and the scope of the “broadcast” chat channel were based on these areas. In between these areas was, as mentioned, not a whole lot, but all of this other space was ripe to be turned into massive combined-arms battlegrounds as forces moved between facilities and towers, and the terrain was just varied and interesting enough to lead to some cool battle scenarios. I have vivid memories of battles around Searhus’s massive volcano crater’s rim, and the epic fights around the many long chokepoint bridges spanning bodies of water all across Auraxis are legendary, for example.

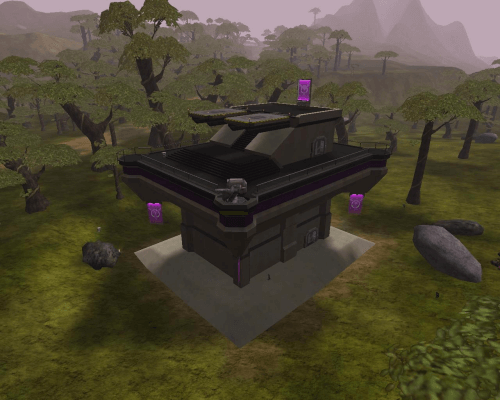

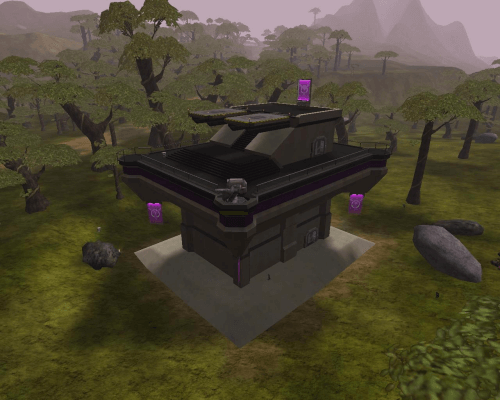

“A nice, quiet VS tower, just waiting to be taken.”

Outside of traveling between them, there were other reasons battles might take place in-between facilities that were directly linked to how taking over facilities worked. Let’s start from the beginning though. Each facility had a relatively small structure called a “tower” just outside of its sphere of influence. There were a few varieties of towers, with some having gun turrets, others having landing pads, but they were all close to identical on the inside. Dominated by a wide staircase wrapping from the basement, which contained spawn tubes and equipment terminals and was protected by a “pain field” to keep would-be enemy spawn campers at bay, up to the roof, with a control console near the top. There was not much to these towers, but they were key in how facility captures worked, as they allowed an attacking force to quickly gain a nearby foothold from which they could respawn and attack the main facility. Unlike facilities, control of the towers would instantly change once the control console was hacked, plus, not being tied to the lattice system, they could be hacked by anyone, at any time. Intense battles in and around towers weren’t uncommon, but they were also some of the more common places for great smaller fights to occur.

“Tower fights could be bloody affairs. Get that loot!”

So, you hacked the door to a tower, made it up (or down, if you decided to land or drop on the roof from an aircraft) to the control console. You hacked it, and control of the tower went to your empire. If there were enemies around, they’d notice this pretty quickly and might immediately begin mounting a response to attempt to take it back from you. In the meantime, you and your allies could you set your sights on the facility itself. While there were other options for tactically deploying around a facility you were attacking, most notably a vehicle called the Advanced Mobile Station (AMS) which could be parked and “deployed” to cloak itself and act as a mobile spawn tube and equipment terminal, ownership of a facility’s tower was definitely a much more solid foothold.

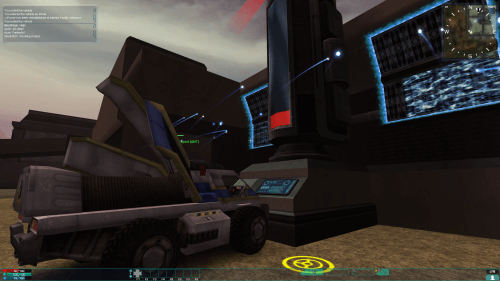

“Hacking a VS controlled facility’s control console.”

Taking a facility worked similarly. There were several different facility designs and layouts, but they were all surrounded by high, castle-like walls with turrets which would act as sentry turrets if unmanned, with only a few entrances on foot – either the large arched gates on either side of the courtyard that allowed vehicles in and out, or via the locked backdoor of the facility. This is where a Galaxy dropship is especially handy, allowing a full squad of troops to effectively bypass the outer defenses of a facility, dropping right into the courtyard or onto the upper levels of the main structure itself. Regardless, assuming you were able to make it into and through the courtyard, you’d make your way into the main facility and eventually find its control console room, usually fairly deep within the complex. Unlike the rather exposed control console of a tower, the control console of a facility was in a small, dedicated room that was much more defensible. Assuming you were then able to get in there and hack the control console, you’d then have to wait for a 15 minute timer to tick down before control of the facility finally changed. During that time, of course, you could expect a defense to mount if there wasn’t already one – enemies would drop in via HART from their sanctuary, arrive by various methods from nearby facilities, and enemies killed in their attempts would respawn there. 15 minutes can feel like a damn long time.

“Arson setting a bunch of Boomers (remote mines) to destroy a generator.”

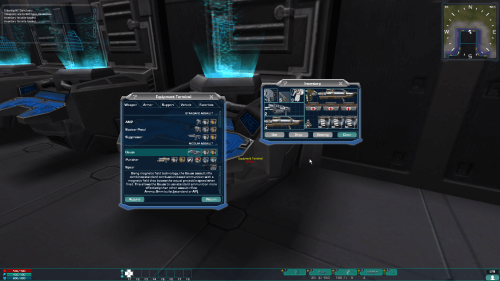

One strategy that was often employed to help ease the burden of attacking a facility was purposely draining the facility of power. Every interactable device in the facility – equipment and vehicle terminals, spawn tubes, turrets, etc. ran on power provided by the facility’s generator, which was in turn fed by a supply of Nanite Technology Units (NTUs.) This power was drained much more quickly by the facility’s auto-repair systems, which would slowly repair any of these devices when damaged or destroyed. Once a facility was completely drained of NTUs, it would lose power and turn neutral, meaning no defenders could respawn there and it could be hacked freely once power was restored. Another version of this tactic involved blowing up the generator itself which would immediately cause the facility to lose power until it could be repaired, but this would also alert everyone that it was under attack as well as requiring it to be repaired before the facility could be back up and online. Still, it could be very effective to strategically take a facility’s generator down to deprive your enemies of the lattice linked benefits they’d get from it. Regardless, these strategies could allow small, coordinated groups to run special ops style “back-hacks” to assault facilities away from the frontline and take them over without much resistance.

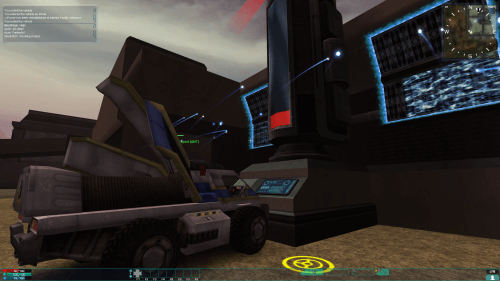

“An ANT refilling the NTU silo at a neutral facility”

One really cool element of the whole facility power system was that if a facility did run out of NTUs, it could be refueled. There was a special vehicle called an Advanced Nanite Transport (ANT) which could be driven out to a warp gate and deployed to fuel its tank, then driven back to a facility and deployed near its NTU silo to refuel it. Making NTU runs after a facility had been drained wasn’t usually too exciting, but making an emergency run during a huge battle could be edge of your seat intense. There were various ways to lessen the chances of your ANT run ending in a glorious, extra-large explosion, such as driving with an escort or even a whole convoy for protection, or using a Galaxy or Lodestar to haul one around in the air, but regardless, a well coordinated assault OR defense often involved accounting for the availability of NTU refuels.

Similarly, there was also a system added early into the game in which some facilities had a special device called a Lattice Logic Unit (LLU) which needed to be physically carried to another facility after a successful hack to complete the change of control rather than waiting out the timer. There were all kinds of conditions and limitations to who could carry the LLU and how – what vehicles they could ride in, etc. The LLU was, of course, a bit of a MacGuffin. It’s real purpose was to generate more battles outside of facilities similarly to those that could take place around ANT runs. While I don’t know how successful this ultimately was, I do recall being involved in some particularly intense battles that revolved around trying to protect or assault an LLU carrier.

“A squad of NC Lightning tanks engaging.”

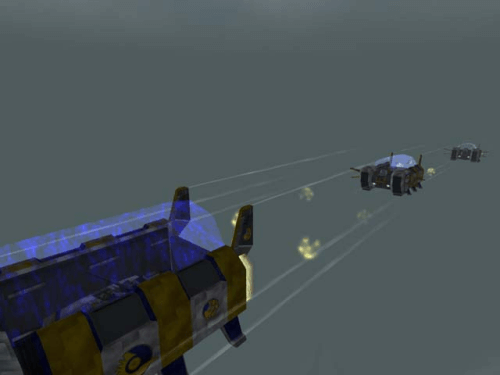

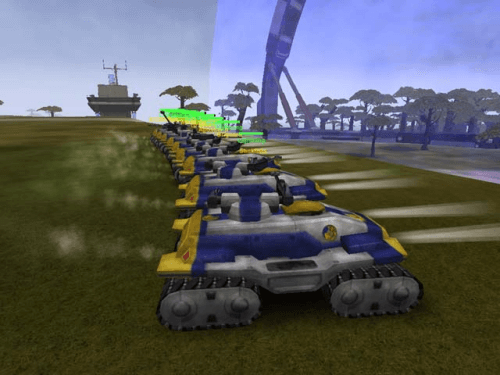

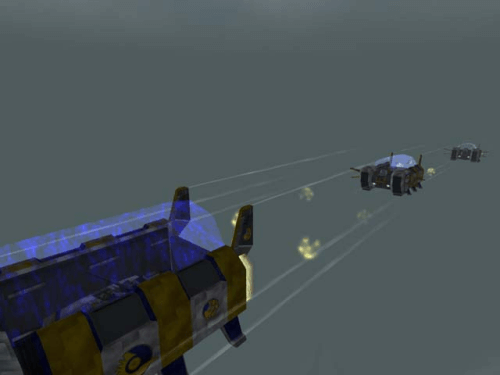

As a quick aside, both of those systems seemed to be there to introduce more opportunity for fights to happen outside of facilities and, of course, using numerous vehicles. While it was common to use vehicles of all sorts to travel between facilities, which is when the most epic vehicle battles took place, and using certain vehicles like Galaxy dropships for infantry drops, AMSes to setup spawn points, and ANTs for refuel runs were very specific but common use-cases, running vehicles that required multiple crew members, like main battle tanks and the fearsome Liberator bomber, along with running multiple vehicles together, tended to be something more of a distraction to my outfit. Something we did for fun, but not something that often felt like it was contributing meaningfully to most battles. Likewise, running the lighter Mosquito and Reaver aircraft seemed like it was used for more quick transport and scouting behind the lines, and solo hunting of enemies. While all of these vehicles could be effective in combat in the right circumstances, due to the way facilities were structured and facility capturing worked, their effectiveness as “force multipliers” was limited.

So, as mentioned above, once you controlled a facility, the lattice link to other connected facilities opened up, expanding the front and allowing you to move on to more facilities. This went on (often involving struggles between all three sides) until eventually one empire controlled the entire continent. This temporarily locked all of the facilities on the continent from being captured, so efforts would usually move to one of the next connected continents. So on, and so forth. Honestly, this larger strategic part of the game was one of the weaker areas of Planetside in my opinion. There wasn’t any real purpose to taking over a continent, or indeed all of Auraxis. Unlike similar MMORPG territory-control based PVP systems, you’re not establishing your own strongholds where you can build housing or shops, or new areas to craft, hunt, or run dungeons, and there’s zero permanence to any of it. Planetside, it seemed, gambled on the fun of the actual fights being enough to inspire players rather than any end goal or rewards. This couldn’t have helped Planetside’s subscription base – it really only took a month or two of playing the game to have seen everything and have it totally figured out, and unlike most MMORPGs, there simply wasn’t enough variety of other diversions to keep players who were bored or just needed a break from cancelling.

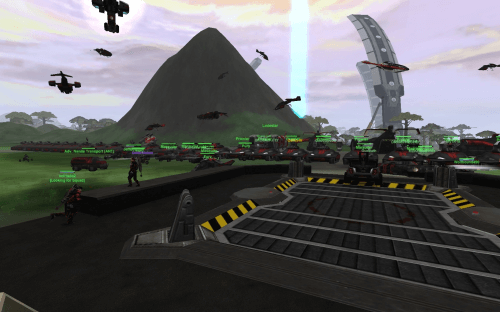

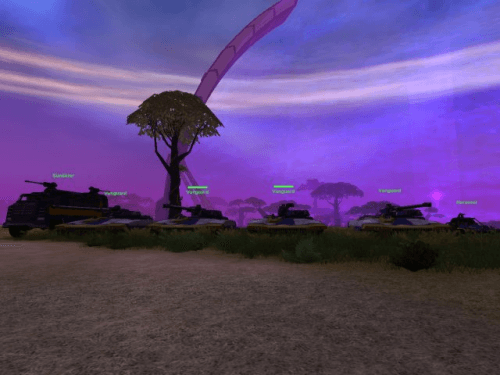

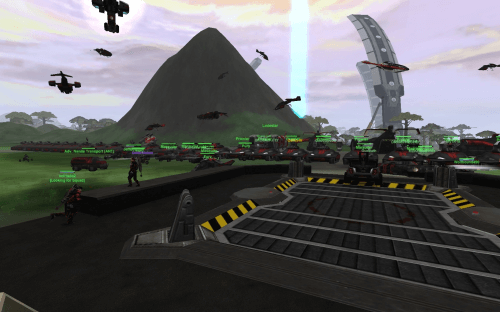

“A massive TR force gathers at a warp gate.”

I didn’t really mention the concept of “zerging” at all, and I should, because it comes up a lot in discussions around Planetside. The “zerg” was an obviously Starcraft-inspired term used to describe the largest masses of players, and “zerging” was the act of joining one of these groups and following them from enemy facility to enemy facility, overwhelming enemy resistance with sheer numbers. Most of the time these huge forces would inevitably meet, meaning that on every contested continent, there was usually at least one incredibly huge, lag inducing, ridiculously chaotic battle. Following the zerg was a way to guarantee access to Planetside’s largest fights, and more importantly, the experience points that came with them, but to many of us this was less exciting than smaller fights, special ops missions, coordinated vehicle runs, and numerous other experiences the sandbox nature of the game could provide. Getting online and following the zerg every night was the entire game to some people, and unsurprisingly, many of them quickly grew to consider Planetside as rather repetitive and dull.

“A group of NC Lodestars hauling Vanguard main battle tanks behind enemy lines.”

That about wraps up my lengthy overview of Planetside’s gameplay. As mentioned, I played the game pretty steadily for its first year or so. In that year, development felt a little slow, especially given the monthly fee we were paying SOE for the privilege, but in reflection it wasn’t too bad. The Liberator bomber was added, along with a dedicated anti-air vehicle called the Skyguard. The aforementioned LLU system was added. They expanded hacking. They added platoons, which could be used to combine 3 squads into one larger unit. They also added the Lodestar, which I’ve mentioned a couple of times now. I do have to wonder just how many of those additions were holdovers that didn’t quite make release, but regardless, content is content. Actually, looking back, one of the issues I think Planetside’s development team had with adding new content to the game is that it was essentially already fairly well designed and balanced upon release. Anything all that interesting that they added to the game was sure to irreversibly alter that balance. Speaking of…

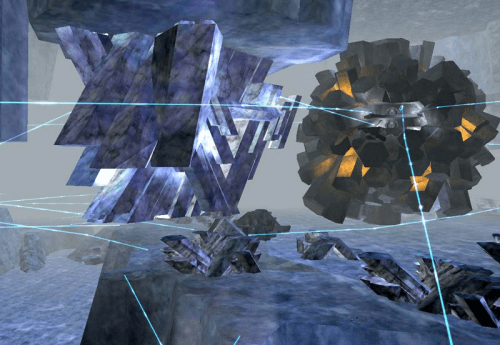

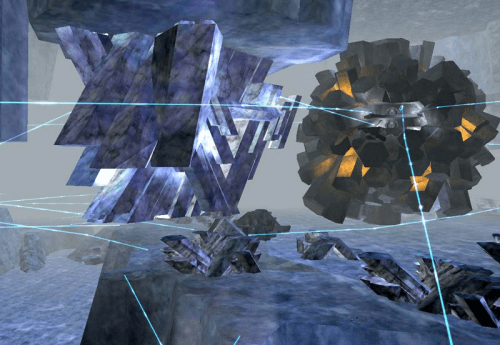

“Core Combat’s caverns looked like nothing else in the game.”

The game’s first and only paid expansion, Core Combat, also came out at around this time. Core Combat added several huge underground cavern maps to Auraxis. These could be accessed via warp gate-like areas called “Geowarps” that were limited in their availability. The main appeal of these caverns was a shift to more CQB-inspired infantry combat, as the caverns featured a lot of cramped areas, a lot of verticality, and relied on teleporters and ziplines for traversal since vehicle usage was limited. While most of my outfit mates were excited about the concept, I don’t think I was alone in being fairly underwhelmed by the cavern-based combat experience. There was at least a reason to go down to the caverns, and that was the new facility module system. You could obtain and charge-up a “module” in a cavern which could then be brought back to the surface and installed at a facility, giving it a particular new benefit, which also extended to any other connected facilities your empire controlled. These benefits were things like adding an energy shield to the otherwise open gate entrances in the walls of your facilities, granting players faster movement speed and reducing spawn times to a facility, and allowing them to pull some of the new “ancient technology” vehicles added with expansion, such as the extremely useful Router (a deployable teleportation system) and the Flail (long distance artillery) from the facility’s vehicle terminals. I totally appreciate a lot of the ideas they were trying to implement with Core Combat, and cavern runs could be a fun diversion for smaller squads, but it ultimately felt like too much of a distraction from the core systems of the game, and a bit of misstep.

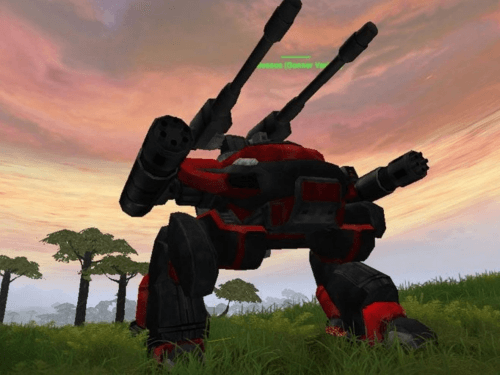

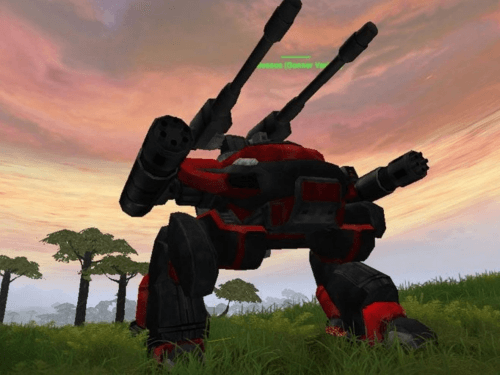

“A TR BFR stomping across the battlefield.”

Still, even more was added later into the game’s life. Beyond things like bug fixes and numerous UI enhancements, they added new vehicles, such as the Fury ATV and new empire specific versions of The Deliverer troop transport. They added a merit/accommodation system and other improved ways to view and track your stats. There was “The Bending” patch that replaced one of the continents (Oshur) with several new smaller “Battle Islands” which each had its own special rules and restrictions, which was kind of neat for variety’s sake, but they also made each continent its own planet, changing the global map to a interstellar map in a rather stupid move. Then, in perhaps the most controversial thing to ever happen in the game, they added huge mech-like vehicles called BattleFrame Robotics (BFRs) which absolutely shook the game to its core. I had mixed feelings about BFRs myself. I mean, the panic instilled by being on foot when a towering BFR stomped onto the battlefield, leaving a path of destruction in its wake, was a totally new addition to the dynamic of the game, and was only topped by having a friendly BFR show up shortly thereafter and watching them go toe-to-toe in an epic scrap. Regardless of how much SOE “nerfed” and otherwise altered BFRs after first introducing them, a vocal part of the community completely hated their addition for reasons ranging from reasonable concerns about the balance and indeed the entire overland combat meta being altered, to simply hating the idea of “unrealistic” mechs being added to their sci-fi vidja game. Boy…

There was more after that, of course, as the game stayed online in one form or another until 2016, but the last time I stepped foot onto the virtual battlefields of Auraxis was around the time the BFRs were finally close to resembling being balanced. I’ve said it before, but Planetside was a special game to me – one where I got really into gaming with a community, and where I made friends I still have today. It was a unique game too, that, like so many online-only games, is sadly now gone to us outside of some unofficial preservation efforts. It’s also survived by Planetside 2, of course, and while Planetside 2 was influenced heavily by the first game and does a good job of respecting what it established, they’re also very different games. It may end up being quite an effort, but I’m hoping to compare and contrast those two games, as well as talk more about Planetside 2 in general, in a future article here. Stay tuned!

Pictures taken from my old NC outfit, The Praetorian Guard’s, archived website, JeffBeefjaw’s Imgur album, which looks quite similar, but from the TR perspective, and some newer pictures acquired while playing around on the PSForever server. Unfortunately the two former sources don’t really show any ACTUAL combat, as few people captured full time back in the day so most screenshots were of points of interest, outfit photo ops, and just dicking around rather than normal gameplay. I also had to grab the original world map, the Core Combat cavern, and the BFR pictures from wherever I could find them.